How would we rebuild the world after an apocalypse?

More than once in our history, humans have come remarkably close to extinction Credit: getty

What if the world gets far too hot? Or enters the next ice age? Where would we go? How would we cope? Astrobiologist Dr Lewis Dartnell has the answers

Contrary to what snowflakes in the West seem to think, we are profoundly lucky to be alive right now.

Never in human history has life been as comfortable, medicine more advanced, poverty rates lower and developed countries so at peace with one another.

This is something to be enjoyed while it lasts, because inevitably it won't. Not only does history tell us that every 1,000 years or so some sort of natural event occurs that wipes out about a third of the global population, we're also overdue the next ice age, which will hit us far worse than that.

Indeed, our eventual demise is all but a certainty. Some find this prospect horrifying; the nihilists among us take comfort in such perspective, but the fact remains that more than 99 per cent of all the species that have ever lived on Earth have gone extinct.

Humans have, however, in our short time since entering existence, managed to narrowly avoid total elimination before. Thrice that we know of, our numbers have dwindled into the thousands or even hundreds; most recently 70,000 years ago when a major climatic shift reduced our population to the "very edge of extinction", as palaeontologist Meave Leakey puts it.

Nature would very quickly reclaim the Earth if there was a mass extinction of humans Credit: getty

Earlier this month, we interviewed astrobiology research scientist Dr Lewis Dartnell about what might cause the next apocalypse (a global pandemic, most probably). He not only studies our origins and the likely causes of our demise, but has also written a book on what the aftermath of a near-total extinction event would look like: The Knowledge: How to Rebuild our World After an Apocalypse.

It throws up the interesting insight that, unlike our hunter-gatherer ancestors who managed (just) to outwit the planet at its most hostile, most of us today would be woefully under-equipped for such an eventuality. Our few survivors would have a very tough time getting things back on track.

Ready to dive into a game of Worst Case Scenario?

How it would happen

Five years before the current outbreak of coronavirus, Dartnell somewhat prophetically hypothesised: "A particularly virulent strain of avian flu finally breached the species barrier and hopped successfully to human hosts, or perhaps was deliberately released in an act of bioterrorism.

"The contagion spread devastatingly quickly in the modern age of high-density cities and intercontinental air travel, and killed a large proportion of the global population before any effective immunisation or even quarantine orders could be implemented. The world as we know it has ended: what now?"

Coronavirus was a disaster waiting to happen Credit: getty

How we would cope

Not well. "People living in developed nations have become disconnected from the processes of the civilisation that supports them," Dartnell says. "Individually, we are astoundingly ignorant of even the basics of the production of food, shelter, clothes, medicine, materials or vital substances."

He tells us: "If people in our modern lives could no longer take for granted that there will be food in the markets or water coming out of taps, we would very soon start leaving our homes and turning violent in our competition for resources. The theory goes, we're only really three days aways from rioting."

Obviously, in the event of a mass-depopulation that left only a fraction of us on the planet, the very fate of humanity would depend on the professions of those people. "If you've got a load of accountants and management consultants you might as well kiss your chances of rebuilding society goodbye," he says. "If you've got nurses, doctors, engineers, mechanics, they'd of course be far more useful than people with conceptual professions." Dartnell counts both himself, an academic, and I, a journalist, among the useless latter.

Interested in improving your chances? Perhaps make a holiday out of it. The Bear Grylls Survival Academy, for one, offers UK-based courses such as its 'Primal Survival Family Adventure' in the South Downs (beargryllssurvivalacademy.com).

Bear Grylls would probably do alright Credit: getty

Agriculture

It took nearly 200,000 years for **** sapiens, the first modern humans, to discover agriculture, and since then it's been a bumpy ride.

Take the Mayan civilization, a highly sophisticated ancient society that was based in Central America. By the eighth century, rather than struggle, the Mayans had gotten too advanced at farming for their own good - enough to spell their downfall.

Rampant deforestation in the short term meant more crops to feed more people, and a thus ballooning population (which carries its own problems). Somewhere approaching the 10th century, the Mayans suddenly deserted their cities. No-one knows why for sure, but the fashionable theory today among many scientists is that localised climate change, brought on by destruction of the rainforests, coupled with overpopulation, famine and probably war, hastened its collapse.

Today, we are witnessing something of a repeat, particularly when it comes to overpopulation, Dartnell points out. "Many of the problems of resource overutilisation and environmental damage - like ocean acidification, pollution, plastic - fundamentally come down to too many humans living unsustainably," he says.

"If there were to be a mass depopulation event, by this warped logic, it would solve a lot of problems."

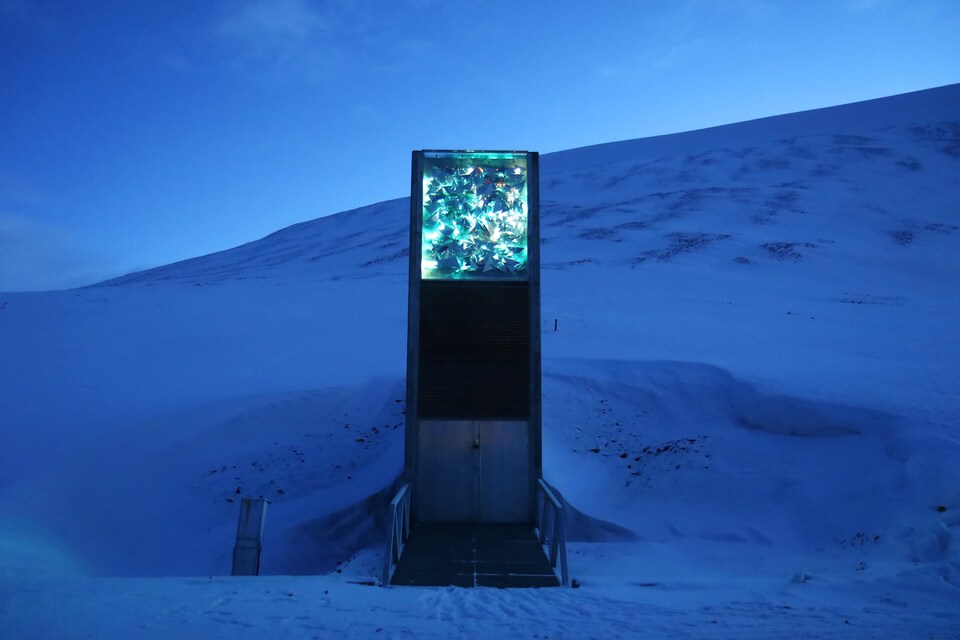

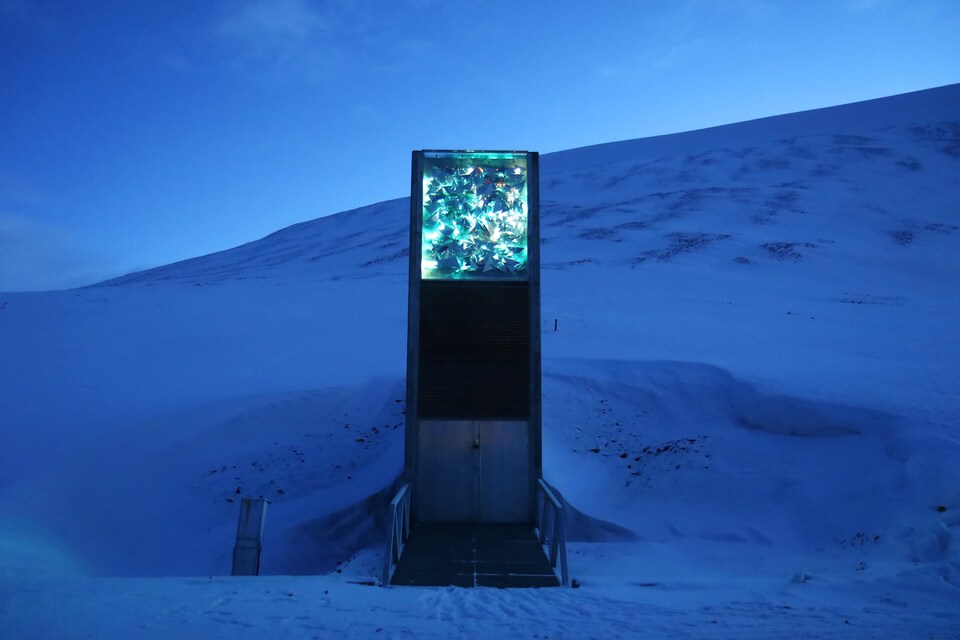

So, you've survived as one of the few and it's time to think about kick-starting agriculture again. Where do you start? By going to Norway, to a snow-covered lair.

Squirrelled away on the northerly archipelago of Svalbard is the Global Seed Vault. Its mission: store enough seeds to ensure genetic diversity among crops around the globe should an apocalypse strike. More than 860,000 samples of around 4,000 plant species are safely stashed in sealed bags in this far-flung Arctic safehouse.

The site even has James Bond-esque safeguards in place: in the event of a power failure, the seldom-opened vault will remain sealed. The permafrost will keep stocks cold. And security measures stipulate that the stored seeds can only be retrieved by the nation that placed them here, ensuring no one can capitalise on another country's agricultural crisis.

Pre-apocalypse, you can't go inside the vault for a poke around, obviously, but there's much else to enjoy in Svalbard as a traveller, particularly the settlement of Longyearbyen: a strange town that experiences 100 days a year without sunlight, where anyone in the world can live visa-free, but where no-one is allowed to die.

Get yourself to Svalbard's Global Seed Vault Credit: istock

How will we fare through the next ice age?

If it's anything like the last one, which ended some 12,000 years ago, the whole of Northern America, Europe and Asia will freeze. A major drop in sea levels would cut off marine channels in regions like the Mediterranean and Australia's Torres Strait, and civilisation as we know it would crumble.

Some of the few humans that did survive the last ice age sheltered in one of the only places on Earth that remained habitable - a slice of land on Africa's south coast near Cape Town - which, conveniently, Telegraph readers have voted to be their favourite city seven times in a row.

What would life become if it was so extremely cold? We don't know, but there's wisdom from the residents of Oymyakon, currently the coldest inhabited place on Earth. When photographer Amos Chapple visited the Russian settlement, where temperatures can sink to as low as -67C and frozen eyelashes are an everyday given, locals told him they turn, for comfort, to "Russki chai" - their term for vodka.

Life is hard in Oymyakon Credit: getty

What if it gets too hot instead?

The fastest temperature rise on Earth came about 55 million years ago and is known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a time when natural greenhouse gasses - exact cause unknown - heated the planet by between 5C to 8C, probably over a few thousand years, to a global average 7 degrees higher than it is today.

Lots of sea species went extinct, but it was great news for biodiversity on land; mammals thrived and it is over this period that primates evolved. Much more recently, phases during which our planet has been slightly hotter than it is now have typically coincided with humanity flourishing, not floundering; the Roman Warm Period being a good example. Even more recently, when the LA Times interviewed residents of what is currently the hottest place on Earth, California's Death Valley, in 2001, they were overwhelmingly enthusiastic about it.

All of which is not to say, of course, that warming is good news for everyone. For us, rising temperatures will result in melting ice caps and rising sea levels, and if that were to happen, you'd be wise to find somewhere virtually impervious to flooding. The Himalayas would work, although the weather can be a little brisk all the way up there. A better bet might be the Bolivian Altiplano, a vast area of high plateau in South America. The whole region lies at an altitude of around 3,750 metres, and what's more, it's a beautiful part of the world.

Could our planet get even hotter than it was during, say, the PETM? In theory, perhaps. According to The Scientific American, were we to experience the "runaway greenhouse effect", a climate event that has never happened on Earth (but may well have on Venus). For this to be possible, we would need to burn ten times the amount of all the fossil fuels we have at our disposal.

In short, powerful and destructive as we humans may consider ourselves to be, there is a limit to how much we can really influence the climate.

The super-rich are preparing already

People have long been building themselves doomsday bunkers - generally the oddballs and conspiracy theorists among us - but in recent years it's a craze that has spread to the elite.

Peter Thiel, the billionaire behind PayPal, is one of many Silicon Valley giants to have snapped up an apocalypse-proof bolthole, having acquired a $13.5m, 500-acre plot on the shores of Lake Wanaka in New Zealand after (somewhat controversially) buying himself citizenship there.

Lovely Lake Wanaka Credit: getty

Thiel chose wisely, not least because it's your favourite country. Two scientists recently ranked the safest places to flee to in the event of an extreme pandemic, and, unsurprisingly, islands were the main focus. New Zealand scored second, after Australia, on the list of suitable options. Naturally isolated from the spread of disease, they were described as excellent places to ride out a pandemic or "other relevant existential threats".

A conspiracy theorist might raise their eyebrows at the notion that of all the major players in the corporate world, it is the tech giants most eager to acquire such bunkers (do they know something we don't know?), but we aren't here to raise such questions.

What would a world be like without humans?

Pretty pleasant, if you don't happen to be one of them. When Telegraph Travel's Greg Dickinson visited Fukushima - eight years after a nuclear disaster cleared the area of inhabitants - he found a landscape both derelict but hopeful.

"This is a place that, probably more so than anywhere else on the planet, offers a glimpse of what happens when humans leave somewhere behind and nature is free to do its thing," he wrote. "Green shoots were growing in the cracks of the pavement; plots where houses were razed after the earthquake were now waist-high with foliage; one home was entirely hidden behind a monstrous plant, creeping across its exterior walls."

Similarly in Chernobyl, 30 years after the worst nuclear disaster in history resulted in a mass evacuation, wild animal and bird species are today roaming what is effectively one of Europe's biggest - if unintentional - wildlife reserves. The European lynx, previously absent, has returned to the area, as have brown bears, alongside thriving numbers of elk, deer and wolves.

Today, you can visit parts of Chernobyl under the supervision of a tour guide, as Telegraph Travel's Oliver Smith did - to see for yourself. Just don't stay too long - it's still rather radioactive.

More than once in our history, humans have come remarkably close to extinction Credit: getty

- Annabel Fenwick Elliott, SENIOR CONTENT EDITOR

What if the world gets far too hot? Or enters the next ice age? Where would we go? How would we cope? Astrobiologist Dr Lewis Dartnell has the answers

Contrary to what snowflakes in the West seem to think, we are profoundly lucky to be alive right now.

Never in human history has life been as comfortable, medicine more advanced, poverty rates lower and developed countries so at peace with one another.

This is something to be enjoyed while it lasts, because inevitably it won't. Not only does history tell us that every 1,000 years or so some sort of natural event occurs that wipes out about a third of the global population, we're also overdue the next ice age, which will hit us far worse than that.

Indeed, our eventual demise is all but a certainty. Some find this prospect horrifying; the nihilists among us take comfort in such perspective, but the fact remains that more than 99 per cent of all the species that have ever lived on Earth have gone extinct.

Humans have, however, in our short time since entering existence, managed to narrowly avoid total elimination before. Thrice that we know of, our numbers have dwindled into the thousands or even hundreds; most recently 70,000 years ago when a major climatic shift reduced our population to the "very edge of extinction", as palaeontologist Meave Leakey puts it.

Nature would very quickly reclaim the Earth if there was a mass extinction of humans Credit: getty

Earlier this month, we interviewed astrobiology research scientist Dr Lewis Dartnell about what might cause the next apocalypse (a global pandemic, most probably). He not only studies our origins and the likely causes of our demise, but has also written a book on what the aftermath of a near-total extinction event would look like: The Knowledge: How to Rebuild our World After an Apocalypse.

It throws up the interesting insight that, unlike our hunter-gatherer ancestors who managed (just) to outwit the planet at its most hostile, most of us today would be woefully under-equipped for such an eventuality. Our few survivors would have a very tough time getting things back on track.

Ready to dive into a game of Worst Case Scenario?

How it would happen

Five years before the current outbreak of coronavirus, Dartnell somewhat prophetically hypothesised: "A particularly virulent strain of avian flu finally breached the species barrier and hopped successfully to human hosts, or perhaps was deliberately released in an act of bioterrorism.

"The contagion spread devastatingly quickly in the modern age of high-density cities and intercontinental air travel, and killed a large proportion of the global population before any effective immunisation or even quarantine orders could be implemented. The world as we know it has ended: what now?"

Coronavirus was a disaster waiting to happen Credit: getty

How we would cope

Not well. "People living in developed nations have become disconnected from the processes of the civilisation that supports them," Dartnell says. "Individually, we are astoundingly ignorant of even the basics of the production of food, shelter, clothes, medicine, materials or vital substances."

He tells us: "If people in our modern lives could no longer take for granted that there will be food in the markets or water coming out of taps, we would very soon start leaving our homes and turning violent in our competition for resources. The theory goes, we're only really three days aways from rioting."

Obviously, in the event of a mass-depopulation that left only a fraction of us on the planet, the very fate of humanity would depend on the professions of those people. "If you've got a load of accountants and management consultants you might as well kiss your chances of rebuilding society goodbye," he says. "If you've got nurses, doctors, engineers, mechanics, they'd of course be far more useful than people with conceptual professions." Dartnell counts both himself, an academic, and I, a journalist, among the useless latter.

Interested in improving your chances? Perhaps make a holiday out of it. The Bear Grylls Survival Academy, for one, offers UK-based courses such as its 'Primal Survival Family Adventure' in the South Downs (beargryllssurvivalacademy.com).

Bear Grylls would probably do alright Credit: getty

Agriculture

It took nearly 200,000 years for **** sapiens, the first modern humans, to discover agriculture, and since then it's been a bumpy ride.

Take the Mayan civilization, a highly sophisticated ancient society that was based in Central America. By the eighth century, rather than struggle, the Mayans had gotten too advanced at farming for their own good - enough to spell their downfall.

Rampant deforestation in the short term meant more crops to feed more people, and a thus ballooning population (which carries its own problems). Somewhere approaching the 10th century, the Mayans suddenly deserted their cities. No-one knows why for sure, but the fashionable theory today among many scientists is that localised climate change, brought on by destruction of the rainforests, coupled with overpopulation, famine and probably war, hastened its collapse.

Today, we are witnessing something of a repeat, particularly when it comes to overpopulation, Dartnell points out. "Many of the problems of resource overutilisation and environmental damage - like ocean acidification, pollution, plastic - fundamentally come down to too many humans living unsustainably," he says.

"If there were to be a mass depopulation event, by this warped logic, it would solve a lot of problems."

So, you've survived as one of the few and it's time to think about kick-starting agriculture again. Where do you start? By going to Norway, to a snow-covered lair.

Squirrelled away on the northerly archipelago of Svalbard is the Global Seed Vault. Its mission: store enough seeds to ensure genetic diversity among crops around the globe should an apocalypse strike. More than 860,000 samples of around 4,000 plant species are safely stashed in sealed bags in this far-flung Arctic safehouse.

The site even has James Bond-esque safeguards in place: in the event of a power failure, the seldom-opened vault will remain sealed. The permafrost will keep stocks cold. And security measures stipulate that the stored seeds can only be retrieved by the nation that placed them here, ensuring no one can capitalise on another country's agricultural crisis.

Pre-apocalypse, you can't go inside the vault for a poke around, obviously, but there's much else to enjoy in Svalbard as a traveller, particularly the settlement of Longyearbyen: a strange town that experiences 100 days a year without sunlight, where anyone in the world can live visa-free, but where no-one is allowed to die.

Get yourself to Svalbard's Global Seed Vault Credit: istock

How will we fare through the next ice age?

If it's anything like the last one, which ended some 12,000 years ago, the whole of Northern America, Europe and Asia will freeze. A major drop in sea levels would cut off marine channels in regions like the Mediterranean and Australia's Torres Strait, and civilisation as we know it would crumble.

Some of the few humans that did survive the last ice age sheltered in one of the only places on Earth that remained habitable - a slice of land on Africa's south coast near Cape Town - which, conveniently, Telegraph readers have voted to be their favourite city seven times in a row.

What would life become if it was so extremely cold? We don't know, but there's wisdom from the residents of Oymyakon, currently the coldest inhabited place on Earth. When photographer Amos Chapple visited the Russian settlement, where temperatures can sink to as low as -67C and frozen eyelashes are an everyday given, locals told him they turn, for comfort, to "Russki chai" - their term for vodka.

Life is hard in Oymyakon Credit: getty

What if it gets too hot instead?

The fastest temperature rise on Earth came about 55 million years ago and is known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a time when natural greenhouse gasses - exact cause unknown - heated the planet by between 5C to 8C, probably over a few thousand years, to a global average 7 degrees higher than it is today.

Lots of sea species went extinct, but it was great news for biodiversity on land; mammals thrived and it is over this period that primates evolved. Much more recently, phases during which our planet has been slightly hotter than it is now have typically coincided with humanity flourishing, not floundering; the Roman Warm Period being a good example. Even more recently, when the LA Times interviewed residents of what is currently the hottest place on Earth, California's Death Valley, in 2001, they were overwhelmingly enthusiastic about it.

All of which is not to say, of course, that warming is good news for everyone. For us, rising temperatures will result in melting ice caps and rising sea levels, and if that were to happen, you'd be wise to find somewhere virtually impervious to flooding. The Himalayas would work, although the weather can be a little brisk all the way up there. A better bet might be the Bolivian Altiplano, a vast area of high plateau in South America. The whole region lies at an altitude of around 3,750 metres, and what's more, it's a beautiful part of the world.

Could our planet get even hotter than it was during, say, the PETM? In theory, perhaps. According to The Scientific American, were we to experience the "runaway greenhouse effect", a climate event that has never happened on Earth (but may well have on Venus). For this to be possible, we would need to burn ten times the amount of all the fossil fuels we have at our disposal.

In short, powerful and destructive as we humans may consider ourselves to be, there is a limit to how much we can really influence the climate.

The super-rich are preparing already

People have long been building themselves doomsday bunkers - generally the oddballs and conspiracy theorists among us - but in recent years it's a craze that has spread to the elite.

Peter Thiel, the billionaire behind PayPal, is one of many Silicon Valley giants to have snapped up an apocalypse-proof bolthole, having acquired a $13.5m, 500-acre plot on the shores of Lake Wanaka in New Zealand after (somewhat controversially) buying himself citizenship there.

Lovely Lake Wanaka Credit: getty

Thiel chose wisely, not least because it's your favourite country. Two scientists recently ranked the safest places to flee to in the event of an extreme pandemic, and, unsurprisingly, islands were the main focus. New Zealand scored second, after Australia, on the list of suitable options. Naturally isolated from the spread of disease, they were described as excellent places to ride out a pandemic or "other relevant existential threats".

A conspiracy theorist might raise their eyebrows at the notion that of all the major players in the corporate world, it is the tech giants most eager to acquire such bunkers (do they know something we don't know?), but we aren't here to raise such questions.

What would a world be like without humans?

Pretty pleasant, if you don't happen to be one of them. When Telegraph Travel's Greg Dickinson visited Fukushima - eight years after a nuclear disaster cleared the area of inhabitants - he found a landscape both derelict but hopeful.

"This is a place that, probably more so than anywhere else on the planet, offers a glimpse of what happens when humans leave somewhere behind and nature is free to do its thing," he wrote. "Green shoots were growing in the cracks of the pavement; plots where houses were razed after the earthquake were now waist-high with foliage; one home was entirely hidden behind a monstrous plant, creeping across its exterior walls."

Similarly in Chernobyl, 30 years after the worst nuclear disaster in history resulted in a mass evacuation, wild animal and bird species are today roaming what is effectively one of Europe's biggest - if unintentional - wildlife reserves. The European lynx, previously absent, has returned to the area, as have brown bears, alongside thriving numbers of elk, deer and wolves.

Today, you can visit parts of Chernobyl under the supervision of a tour guide, as Telegraph Travel's Oliver Smith did - to see for yourself. Just don't stay too long - it's still rather radioactive.