By Chris Baraniuk 22nd August 2017

In the 20th Century, we had information campaigns, fallout shelters, sirens and widespread awareness of the nuclear threat. Do we need a revival of ‘civil defence’ today?

I

In the event of nuclear war, the British government has at its disposal at least one bunker hidden away in the very heart of London. It’s called Pindar. It shares its name with an ancient Greek poet – but the reference is chilling.

It is said that in 335 BC, Alexander the Great demolished the city of Thebes and left only Pindar’s house standing – spared in thanks for some of his poems, which praised the Greek king’s ancestor.

We don’t talk about the bomb dropping or what we might do in the aftermath these days, but that needs to change – Alex Wellerstein

The implication, of course, is that even if London were to be flattened in a nuclear exchange, Pindar would survive. Whether the building has been specifically designed for this is not known. Only a few photos of the complex have ever been published – the fact that they were taken within Pindar was confirmed by the Ministry of Defence in its response to a Freedom of Information Act request.

As well as ultra-safe military headquarters, Pindar offers “continuity of government” – it is part of state plans to ensure authority can prevail even during and after extreme catastrophes. But the capacity for military leaders and senior politicians to outfox disaster is one thing. What about the public they are meant to be protecting and representing? Are we prepared?

A fallout shelter in New York (Credit: AFP/Getty Images)

That is the question that most preoccupies Alex Wellerstein at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. On continuity of government he says, “I’m not interested in that… that’s their problem.”

Wellerstein recently announced that he and his colleagues are taking part in a project to reinvent civil defence. That is, the methods and information campaigns designed to help the public protect themselves in the event of a military attack or natural disaster.

Read more:

After all, there remain about 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world today, the vast majority owned by Russia and the United States. The leaders of both countries recently agreed with one another that relations between their states were at a dangerously low point.

Although Wellerstein acknowledges that nuclear war or a small-scale nuclear detonation by a rogue state or terrorist group is extremely unlikely, he believes there is still value in being prepared just in case.

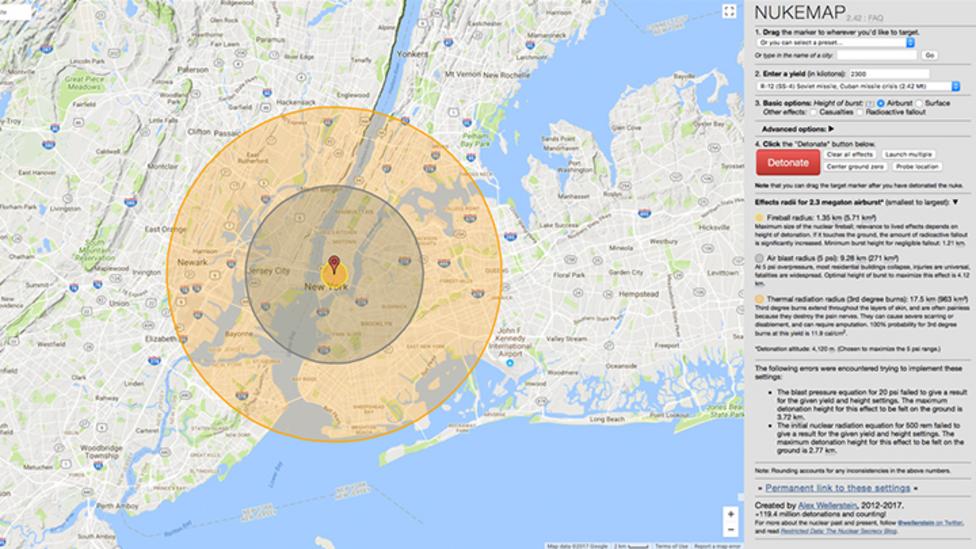

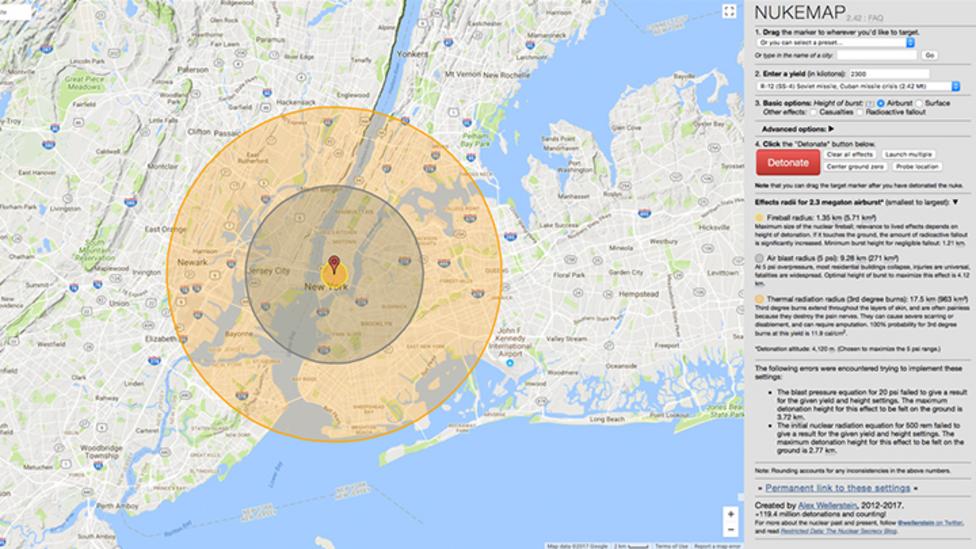

Nukemap, a modified version of Google Maps, tells the user the impact of a nuclear blast (Credit: Alex Wellerstein)

One of Wellerstein’s previous projects was Nukemap: a modified version of Google Maps that tells the user the basic effects of the blast – from the nuclear weapon of their choice – around any location on Earth, including large cities.

The idea is to encourage people to put the nuclear threat into familiar terms, making it seem more real. This is because many scoff at the alleged impotence of civil defence – “they delight in laughing at this stuff,” he explains. And now Wellerstein is planning far more visceral tools.

“Imagine you could put on a [virtual reality] headset,” he says. “You’re looking at the skyline of Manhattan and you see a nuclear weapon go off. Imagine you see this mushroom cloud going up in front of you.

“Does that make it more tangible?”

The advice can be as simple as staying indoors instead of driving out of the affected area

His new project will consider all kinds of materials made with a similar purpose, he says. For example, he suggests the idea of graphic novels designed to impart knowledge about what can be done to improve chances of survival after nuclear attack.

The advice can be as simple as staying indoors instead of trying to drive out of the affected area. This is because roads in crisis situations often become jammed with traffic – this often happens following hurricane warnings, for instance. And when a nuclear bomb goes off, it can suck up lots of dust and debris and irradiates it before spewing this invisible ‘fallout’ out over the surrounding land.

“In the middle of a building, the protection factor goes up dramatically,” explains Wellerstein. “You stay there for a few hours and your radiation risk decreases dramatically.”

A 'shelter' sign at the entrance to a subway station in Seoul, South Korea (Credit: Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

As North Korea continues to demonstrate its increasing capability for launching a nuclear missile that could reach the US and tensions rise between the country’s two leaders, some communities within range of its missiles are beginning to take preparations more seriously. In Japan, villages have been staging nuclear attack drills. Hawaii has revised its guidelines for the public on what to do in the event of a nuclear explosion, as have some local authorities on the US west coast. One of the areas directly threatened by North Korea, the US territory of Guam, has also recently issued instructions about how to cope with radiation (see "Armageddon advice", below). Meanwhile, the US Department of Homeland Security also has recently redesigned its website called Ready.gov, which includes a section on nuclear blasts.

In other countries, the importance of civil defence has fallen off the agenda in recent years. By the 1980s, the UK, had developed a range of civil defence preparedness measures, some of which – regional controllers situated around the country – would have helped ensure continuity of government. Others, such as air raid sirens and information campaigns, were directed specifically at the public.

The sirens, for instance, were situated at thousands of locations. They could have been used to warn of an impending missile strike or to sound the all-clear when radiation levels had died down.

Would the Cold War infrastructure really have been useful if an all-out nuclear exchange had taken place? Thankfully, it never had to be tested in a real scenario.

“The problem with this particular issue is that it is very different from other types of emergencies,” says Patricia Lewis, director of the international security department at policy institute Chatham House. “It is overwhelming.”

In the past, civil defence in Britain was poorly funded, limited in scope and late to recognise very real threats, according to University of Essex historian Matthew Grant who has covered the topic in his book, After the Bomb: Civil Defence and Nuclear War in Britain, 1945-68.

And as Jennifer Cole at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) explains, nuclear war is no longer on the UK’s “National Risk Register” – although the likelihood of a nuclear bomb being detonated by a terrorist group is thought to be “low but not negligible”.

“A nuclear strike isn’t a reasonable worst-case scenario anymore,” she says.

An art installation in Bulgaria to mark the Chernobyl disaster, which showed just how harmful and long-lasting radiation can be (Credit: AFP/Nikolay Doychinov)

Her colleague at RUSI, Tom Plant, also notes that Britain’s Trident submarines – armed with nuclear warheads – are currently at a readiness state of several days’ “notice to fire”. At the height of the Cold War, missiles could have been launched in 15 minutes.

“We’re not in the prevailing circumstances of the Cold War where we are in a perceived high level of threat,” he says.

Much of the planning and preparedness that was set up by 20th Century governments has fallen away

Without that overbearing threat, much of the planning and preparedness that was set up by 20th Century governments has either fallen away or been subsumed into other crisis management plans. Schemes for how to deal with severe flooding, terrorist attacks or other events that may displace large numbers of people have likely drawn on the old Cold War planning, says Cole.

What is in place today? The key regulations in Britain are the Radiation (Emergency Preparedness and Public Information) Regulations – or 'Reppir'. Take, for instance, Portsmouth and Southampton. Both British cities are places where nuclear reactor-powered submarines may dock. As such, the city councils have a detailed emergency plan under Reppir to adhere to should an accident cause radioactivity to be dispersed into the local area. The plan notes several times that the reactors themselves could not cause a nuclear explosion.

Gas masks and other emergency equipment inside the subway in Seoul, South Korea (Credit: Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

The naval base at Portsmouth even has one of the old air raid sirens, which it routinely tests, in case it is needed during an accident. Elsewhere in the UK, other siren systems are in place, to warn about chemical hazards from factories for example.

The question of how much one can do to limit the consequences of a nuclear bomb still lingers.

Certainly, there are many places in the world where nuclear shelters remain, including New York. But there, some of the shelters have since been converted into other facilities making them far less suitable as refuges should a nuclear weapon go off nearby.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) regularly considers the response it could offer to various nations following all sorts of disasters – including the detonation of a nuclear weapon.

“If we look at the impact site minutes after impact,” explains Johnny Nehme, head of the weapon contamination unit, “there is almost nothing that could be done.”

“The only humanitarian assistance that I could foresee is weeks later.”

Tinned food from inside a former nuclear bunker owned by the British government, near Ballymena in Northern Ireland (Credit: AFP/Getty Images)

He also points out that in a war situation, it is possible that borders would be closed and flights grounded, severely limiting the ability of humanitarian organisations to help survivors.

The grim aftermath of a nuclear detonation in a modern city – and the limited ability of humanitarian groups, emergency services and government to assist – makes this terrible scenario seem hopeless to some. But for Alex Wellerstein, and other proponents of civil defence, there actually is a glimmer of hope: a possibility for citizens to increase their chances of survival if they are better prepared and well-informed.

It’s not something anybody really wants to think about. But if the unimaginable happens, maybe having thought about it – even just a little – will be what gives us our best chance.

In the 20th Century, we had information campaigns, fallout shelters, sirens and widespread awareness of the nuclear threat. Do we need a revival of ‘civil defence’ today?

I

In the event of nuclear war, the British government has at its disposal at least one bunker hidden away in the very heart of London. It’s called Pindar. It shares its name with an ancient Greek poet – but the reference is chilling.

It is said that in 335 BC, Alexander the Great demolished the city of Thebes and left only Pindar’s house standing – spared in thanks for some of his poems, which praised the Greek king’s ancestor.

We don’t talk about the bomb dropping or what we might do in the aftermath these days, but that needs to change – Alex Wellerstein

The implication, of course, is that even if London were to be flattened in a nuclear exchange, Pindar would survive. Whether the building has been specifically designed for this is not known. Only a few photos of the complex have ever been published – the fact that they were taken within Pindar was confirmed by the Ministry of Defence in its response to a Freedom of Information Act request.

As well as ultra-safe military headquarters, Pindar offers “continuity of government” – it is part of state plans to ensure authority can prevail even during and after extreme catastrophes. But the capacity for military leaders and senior politicians to outfox disaster is one thing. What about the public they are meant to be protecting and representing? Are we prepared?

A fallout shelter in New York (Credit: AFP/Getty Images)

That is the question that most preoccupies Alex Wellerstein at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. On continuity of government he says, “I’m not interested in that… that’s their problem.”

Wellerstein recently announced that he and his colleagues are taking part in a project to reinvent civil defence. That is, the methods and information campaigns designed to help the public protect themselves in the event of a military attack or natural disaster.

Read more:

- The monster atomic bomb that was too big to use

- The secret nuclear bunker built as the UK's last hope

- The greatest threats to humanity as we know it

After all, there remain about 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world today, the vast majority owned by Russia and the United States. The leaders of both countries recently agreed with one another that relations between their states were at a dangerously low point.

Although Wellerstein acknowledges that nuclear war or a small-scale nuclear detonation by a rogue state or terrorist group is extremely unlikely, he believes there is still value in being prepared just in case.

Nukemap, a modified version of Google Maps, tells the user the impact of a nuclear blast (Credit: Alex Wellerstein)

One of Wellerstein’s previous projects was Nukemap: a modified version of Google Maps that tells the user the basic effects of the blast – from the nuclear weapon of their choice – around any location on Earth, including large cities.

The idea is to encourage people to put the nuclear threat into familiar terms, making it seem more real. This is because many scoff at the alleged impotence of civil defence – “they delight in laughing at this stuff,” he explains. And now Wellerstein is planning far more visceral tools.

“Imagine you could put on a [virtual reality] headset,” he says. “You’re looking at the skyline of Manhattan and you see a nuclear weapon go off. Imagine you see this mushroom cloud going up in front of you.

“Does that make it more tangible?”

The advice can be as simple as staying indoors instead of driving out of the affected area

His new project will consider all kinds of materials made with a similar purpose, he says. For example, he suggests the idea of graphic novels designed to impart knowledge about what can be done to improve chances of survival after nuclear attack.

The advice can be as simple as staying indoors instead of trying to drive out of the affected area. This is because roads in crisis situations often become jammed with traffic – this often happens following hurricane warnings, for instance. And when a nuclear bomb goes off, it can suck up lots of dust and debris and irradiates it before spewing this invisible ‘fallout’ out over the surrounding land.

“In the middle of a building, the protection factor goes up dramatically,” explains Wellerstein. “You stay there for a few hours and your radiation risk decreases dramatically.”

A 'shelter' sign at the entrance to a subway station in Seoul, South Korea (Credit: Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

As North Korea continues to demonstrate its increasing capability for launching a nuclear missile that could reach the US and tensions rise between the country’s two leaders, some communities within range of its missiles are beginning to take preparations more seriously. In Japan, villages have been staging nuclear attack drills. Hawaii has revised its guidelines for the public on what to do in the event of a nuclear explosion, as have some local authorities on the US west coast. One of the areas directly threatened by North Korea, the US territory of Guam, has also recently issued instructions about how to cope with radiation (see "Armageddon advice", below). Meanwhile, the US Department of Homeland Security also has recently redesigned its website called Ready.gov, which includes a section on nuclear blasts.

In other countries, the importance of civil defence has fallen off the agenda in recent years. By the 1980s, the UK, had developed a range of civil defence preparedness measures, some of which – regional controllers situated around the country – would have helped ensure continuity of government. Others, such as air raid sirens and information campaigns, were directed specifically at the public.

The sirens, for instance, were situated at thousands of locations. They could have been used to warn of an impending missile strike or to sound the all-clear when radiation levels had died down.

Would the Cold War infrastructure really have been useful if an all-out nuclear exchange had taken place? Thankfully, it never had to be tested in a real scenario.

“The problem with this particular issue is that it is very different from other types of emergencies,” says Patricia Lewis, director of the international security department at policy institute Chatham House. “It is overwhelming.”

In the past, civil defence in Britain was poorly funded, limited in scope and late to recognise very real threats, according to University of Essex historian Matthew Grant who has covered the topic in his book, After the Bomb: Civil Defence and Nuclear War in Britain, 1945-68.

And as Jennifer Cole at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) explains, nuclear war is no longer on the UK’s “National Risk Register” – although the likelihood of a nuclear bomb being detonated by a terrorist group is thought to be “low but not negligible”.

“A nuclear strike isn’t a reasonable worst-case scenario anymore,” she says.

An art installation in Bulgaria to mark the Chernobyl disaster, which showed just how harmful and long-lasting radiation can be (Credit: AFP/Nikolay Doychinov)

Her colleague at RUSI, Tom Plant, also notes that Britain’s Trident submarines – armed with nuclear warheads – are currently at a readiness state of several days’ “notice to fire”. At the height of the Cold War, missiles could have been launched in 15 minutes.

“We’re not in the prevailing circumstances of the Cold War where we are in a perceived high level of threat,” he says.

Much of the planning and preparedness that was set up by 20th Century governments has fallen away

Without that overbearing threat, much of the planning and preparedness that was set up by 20th Century governments has either fallen away or been subsumed into other crisis management plans. Schemes for how to deal with severe flooding, terrorist attacks or other events that may displace large numbers of people have likely drawn on the old Cold War planning, says Cole.

What is in place today? The key regulations in Britain are the Radiation (Emergency Preparedness and Public Information) Regulations – or 'Reppir'. Take, for instance, Portsmouth and Southampton. Both British cities are places where nuclear reactor-powered submarines may dock. As such, the city councils have a detailed emergency plan under Reppir to adhere to should an accident cause radioactivity to be dispersed into the local area. The plan notes several times that the reactors themselves could not cause a nuclear explosion.

Gas masks and other emergency equipment inside the subway in Seoul, South Korea (Credit: Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

The naval base at Portsmouth even has one of the old air raid sirens, which it routinely tests, in case it is needed during an accident. Elsewhere in the UK, other siren systems are in place, to warn about chemical hazards from factories for example.

The question of how much one can do to limit the consequences of a nuclear bomb still lingers.

Certainly, there are many places in the world where nuclear shelters remain, including New York. But there, some of the shelters have since been converted into other facilities making them far less suitable as refuges should a nuclear weapon go off nearby.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) regularly considers the response it could offer to various nations following all sorts of disasters – including the detonation of a nuclear weapon.

“If we look at the impact site minutes after impact,” explains Johnny Nehme, head of the weapon contamination unit, “there is almost nothing that could be done.”

“The only humanitarian assistance that I could foresee is weeks later.”

Tinned food from inside a former nuclear bunker owned by the British government, near Ballymena in Northern Ireland (Credit: AFP/Getty Images)

He also points out that in a war situation, it is possible that borders would be closed and flights grounded, severely limiting the ability of humanitarian organisations to help survivors.

The grim aftermath of a nuclear detonation in a modern city – and the limited ability of humanitarian groups, emergency services and government to assist – makes this terrible scenario seem hopeless to some. But for Alex Wellerstein, and other proponents of civil defence, there actually is a glimmer of hope: a possibility for citizens to increase their chances of survival if they are better prepared and well-informed.

It’s not something anybody really wants to think about. But if the unimaginable happens, maybe having thought about it – even just a little – will be what gives us our best chance.